The Cincinnati Kid

| The Cincinnati Kid | |

|---|---|

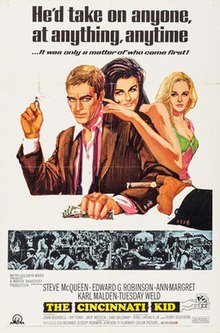

Theatrical release poster | |

| Directed by | Norman Jewison |

| Screenplay by | Ring Lardner Jr. Terry Southern |

| Based on | The Cincinnati Kid 1963 novel by Richard Jessup |

| Produced by | Martin Ransohoff |

| Starring | Steve McQueen Edward G. Robinson Ann-Margret Karl Malden Tuesday Weld |

| Cinematography | Philip H. Lathrop |

| Edited by | Hal Ashby |

| Music by | Lalo Schifrin |

Production companies | |

| Distributed by | Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer |

Release dates |

|

Running time | 113 minutes[1] |

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

| Budget | $3,333,000[2] |

| Box office | $7 million (rentals)[3] |

The Cincinnati Kid is a 1965 American drama film directed by Norman Jewison. It tells the story of Eric "The Kid" Stoner, a young Depression-era poker player, as he seeks to establish his reputation as the best. This quest leads him to challenge Lancey "The Man" Howard, an older player widely considered to be the best, culminating in a climactic final poker hand between the two.

The script, adapted from Richard Jessup's 1963 novel of the same name, was written by Ring Lardner Jr. and Terry Southern; it was Lardner's first major studio work since his 1947 blacklisting as one of The Hollywood Ten.[4] The film stars Steve McQueen in the title role and Edward G. Robinson as Howard. Director Jewison, who replaced Sam Peckinpah shortly after filming began,[4] describes The Cincinnati Kid as his "ugly duckling" film. He considers it the film that allowed him to make the transition from the lighter comedic films he had been making and take on more serious films and subjects.[5]

The film garnered mixed reviews from critics on its initial release. Joan Blondell earned a Golden Globe nomination for her performance as Lady Fingers.

Plot

[edit]Eric Stoner is "The Cincinnati Kid", an up-and-coming poker player in 1930s New Orleans. He hears that Lancey Howard, an old master of the game, is in town, and sees it as his chance to achieve recognition as the new king of five-card stud.

Before they square off, Howard arranges a tune-up game with wealthy, corrupt William Jefferson Slade. For a dealer, he agrees to the services of Shooter, renowned for his integrity and a good friend of the Kid. Howard wins $6,000 from the prideful Slade in a 30-hour game, angering the man enough to seek to get even.

Slade then tries to bribe Shooter with the proceeds of a $25,000 bet into cheating in the Kid's favor when he and Howard meet. Shooter declines, but Slade calls in Shooter's markers worth $12,000, and blackmails him by threatening to reveal damaging information about Shooter's wife, Melba. Slade then throws in canceling the markers as a goose. Shooter agonizes over his decision, having spent the last 25 years building a reputation for honesty. Eventually, however, he caves in.

Meantime, even though Melba and the Kid's girl Christian are close friends, Melba tries to seduce him while Christian is visiting her parents. Out of respect for Shooter, he rebuffs her and spends the day before the game with Christian at her family's farm.

Back in New Orleans the next day the big game begins. It starts with six players, including Shooter playing as he deals, and a relief dealer, Lady Fingers, a popular but faded gambling diva. Howard busts an overconfident player called Pig, then Shooter bows out but remains as the dealer. Later, Yeller and Sokal also drop out. After a few unlikely wins, the Kid abruptly folds what would have been a winning hand and calls for a break. He then privately confronts Shooter, who admits to being forced into cheating by Slade. The Kid insists he can win on his own and tells Shooter to deal straight or he will blow the whistle, destroying Shooter's reputation. Before the game resumes, Melba succeeds in seducing the Kid, only to have Christian make a surprise visit and catch them after the fact. She walks out broken.

When the game resumes the Kid maneuvers to have Shooter replaced by Lady Fingers, claiming Shooter is ill. He then wins several major pots from Howard, who is visibly losing confidence. The Kid is clearly ready to break him.

Over a massive pot, the Kid is confident enough of his full house of aces over tens to place a $5,000 marker with Howard, only to have Lady Fingers, an ex-lover of Howard’s, deal Howard a queen-high straight flush. Howard then chastises the Kid, telling him that he will always be "second best" as long as Howard is around. Leaving the game, the Kid unexpectedly runs into Christian, and they embrace.

Alternative versions

[edit]In some cuts, the film ends with a freeze-frame on Steve McQueen's face following a penny-pitching loss to a brash young shoeshine boy who had been seeking, unsuccessfully, to “cut” him earlier in the movie. Turner Classic Movies and the DVD feature the ending with Christian. Jewison wanted to end the film with the freeze-frame but was overruled by the producer.[5]

A cockfight scene was cut by British censors.[6]

Cast

[edit]- Steve McQueen as Eric "The Kid" Stoner

- Edward G. Robinson as Lancey "The Man" Howard

- Ann-Margret as Melba

- Karl Malden as Shooter

- Tuesday Weld as Christian Rudd

- Joan Blondell as Lady Fingers

- Rip Torn as Slade

- Jack Weston as Pig

- Cab Calloway as Yeller

- Jeff Corey as Hoban

- Theo Marcuse as Felix

- Milton Selzer as Sokal

- Karl Swenson as Mr. Rudd

- Émile Genest as Cajun

- Ron Soble as Danny

- Irene Tedrow as Mrs. Rudd

- Midge Ware as Mrs. Slade

- Dub Taylor as the First Dealer

- Sweet Emma Barrett as the Blues Singer (uncredited)

- Robert DoQui as Philly

- Ken Grant as Shoeshine Boy

Production

[edit]The Cincinnati Kid was filmed on location in New Orleans, Louisiana, a change from the original St. Louis, Missouri, setting of the novel. Spencer Tracy was cast as Lancey Howard, but ill health forced him to withdraw from the film.[7] Sam Peckinpah was hired to direct;[4] producer Martin Ransohoff fired him shortly after filming began[5] for "vulgarizing the picture".[8] Peckinpah's version was to be shot in black-and-white to give the film a 1930s period feel. Jewison scrapped the black-and-white footage, feeling it was a mistake to shoot a film with the red and black of playing cards in greyscale. He did mute the colors throughout, both to evoke the period and to help pop the card colors when they appeared.[5] Strother Martin, who appears early in the film, but is never seen again, said he was fired after Jewison replaced Peckinpah.[9] McQueen's fee for the film was $350,000[2]

The film features a theme song performed by Ray Charles,[10] the Eureka Brass Band performing a second line parade, and a scene in Preservation Hall with Emma Barrett (vocalist and pianist), Punch Miller (trumpet), Paul Crawford (trombone), George Lewis (clarinet), Cie Frazier (drums) and Allan Jaffe (helicon).

Notes on the game

[edit]- When reciting the rules, Shooter clearly states "no string bets", although players (including Howard) go on to make string bets during the game.

- The game is open stakes. This is unusual in modern times and almost never allowed in casinos, but permissible in home games and was common for the time period of the film.[11][12]

- The unlikely nature of the final hand is discussed by Anthony Holden in his book Big Deal: A Year as a Professional Poker Player: "The odds against any full house losing to any straight flush, in a two-handed game, are 45,102,781 to 1," with Holden continuing that the odds against the particular final hand in the movie are astronomical (as both hands include 10s). Holden states that the chances of both such hands appearing in one deal are "a laughable" 332,220,508,619 to 1 (more than 332 billion to 1 against) and goes on: "If these two played 50 hands of stud an hour, eight hours a day, five days a week, the situation would arise about once every 443 years."

Release

[edit]The world premiere was held at the Saenger Theatre in New Orleans on October 15, 1965, with a nationwide release on October 27. The film opened in Los Angeles on November 5.[13]

Home media

[edit]The television premiere of The Cincinnati Kid was on February 11, 1971, when it was broadcast on the CBS Thursday Night Movie.[14] It was released on Region 1 DVD on May 31, 2005. The DVD features a commentary track by director Norman Jewison, commentary on selected scenes from Celebrity Poker Showdown hosts Phil Gordon and Dave Foley and The Cincinnati Kid Plays According to Hoyle, a promotional short featuring magician Jay Ose. A Blu-ray disc was released on June 14, 2011.[15] With the release of the film on DVD, one modern reviewer said the film "is as hip now as when it was released in 1965",[16] and another cited McQueen as "effortlessly watchable as the Kid, providing a masterclass in the power of natural screen presence over dialogue", and Robinson as "simply fantastic".[17] Poker author Michael Wiesenberg calls The Cincinnati Kid "one of the greatest poker movies of all time".[18]

Soundtrack

[edit]Reception

[edit]Critical response

[edit]Upon its 1965 release, The Cincinnati Kid was favorably reviewed by Variety, which wrote, "Martin Ransohoff has constructed a taut, well-turned-out production. In Steve McQueen he has the near-perfect delineator of the title role. Edward G. Robinson is at his best in some years as the aging, ruthless Lancey Howard...."[19]

Howard Thompson of The New York Times called the film a "respectably packaged drama" that is "strictly for those who relish—or at least play—stud poker", and notes that the "film pales beside The Hustler, to which it bears a striking similarity of theme and characterization".[20]

Time magazine also noted the similarities to The Hustler, writing that "nearly everything about Cincinnati Kid is reminiscent" of that film, but falls short in the comparison, in part because of the subject matter.[21]

Director Jewison can put his cards on the table, let his camera cut suspensefully to the players' intent faces, but a pool shark sinking a tricky shot into a side pocket undoubtedly offers more range. Kid also has a less compelling subplot. Away from the table, McQueen gambles on a blonde (Tuesday Weld) and on the integrity of his dealer pal, Karl Malden. Pressure comes from a conventionally vicious Southern gentleman (Rip Torn), whose pleasures include a Negro mistress, a pistol range adjacent to his parlor, and fixed card games. As Malden's wife, Ann-Margret spells trouble of another kind, though her naive impersonation of a wicked, wicked woman recalls the era when the femme fatale wore breastplates lashed together with spider web. By the time all the bets are in, Cincinnati Kid appears to hold a losing hand.

A retrospective review published in 2011 by the New York State Writers Institute of the University at Albany also noted the similarities the film has to The Hustler, but in contrast said The Cincinnati Kid's "stylized realism, dreamlike color, and detailed subplots give [the film] a dramatic complexity and self-awareness that The Hustler lacks".[4]

Through 2023 The Cincinnati Kid holds an 87% "Fresh" rating on Rotten Tomatoes from 23 reviews, with an average user rating of 7.6/10.[22]

Recognition

[edit]Joan Blondell was singled out for her performance as Lady Fingers, with an award from the National Board of Review of Motion Pictures and a Golden Globe nomination for Best Supporting Actress[broken anchor]. Motion Picture Exhibitor magazine nominated Robinson for its Best Supporting Actor Laurel Award.

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ "AFI Catalog: The Cincinnati Kid (1965)". American Film Institute. Archived from the original on January 25, 2021. Retrieved May 18, 2020.

- ^ a b THE CINCINNATI KID, MGM 1965 stevemcqueen.org. Retrieved December 30, 2024.

- ^ This figure consists of anticipated rentals accruing distributors in North America. See "Big Rental Pictures of 1965", Variety, 5 January 1966, pg 6.

- ^ a b c d Hartman, Steven. "Film Notes: Cincinnati Kid". New York State Writers Institute Film Notes. University at Albany. Archived from the original on 2011-08-29. Retrieved 2009-01-19.

- ^ a b c d Jewison, Norman (2005). The Cincinnati Kid director commentary (DVD). Turner Entertainment.

- ^ "The Cincinnati Kid Review". Channel4.com. BBC4. Archived from the original on 2007-10-27. Retrieved 2007-07-29.

- ^ Deschner, David (1993). The Complete Films of Spencer Tracy. Citadel Press. p. 57.

- ^ Carroll, E. Jean (March 1982). "Last of the Desperadoes: Dueling with Sam Peckinpah". Rocky Mountain Magazine.

- ^ Scott, Vernon (20 May 1978). "Actor lives in fear of snips". Lodi News-Sentinel. Archived from the original on 6 May 2016. Retrieved 20 April 2016.

- ^ The Cincinnati Kid opening credits

- ^ Ciaffone, Robert. "Robert's Rules of Poker — Version 6". Pokercoach.us. Archived from the original on 2007-08-10. Retrieved 2007-08-04.

- ^ Cooke, Roy (2005-10-04). "A Famous Movie Poker Hand". Card Player. Archived from the original on 2009-06-09. Retrieved 2009-10-20.

- ^ "AFI Catalog: The Cincinnati Kid (1965)". American Film Institute. Archived from the original on January 25, 2021. Retrieved May 18, 2020.

- ^ "TV Today and Tonight". Sarasota Herald-Tribune. (Feb. 11, 1971): p. 28.

- ^ "Cincinnati Kid, The (DVD)". Barnes & Noble. Archived from the original on January 17, 2013. Retrieved 2007-09-13.

- ^ Cullum, Brett (June 13, 2005). "DVD Verdict Review: The Cincinnati Kid". DVD Verdict. Archived from the original on January 19, 2008. Retrieved 2007-09-11.

- ^ Sutton, Mike (June 20, 2005). "The Cincinnati Kid". DVD Times. Archived from the original on 2013-04-20. Retrieved 2007-09-11.

- ^ Weisenberg, Michael (August 23, 2005). "Implausible Play in The Cincinnati Kid? A play-by-play analysis of a highly unlikely poker hand". Card Player Magazine. Archived from the original on April 13, 2014. Retrieved August 10, 2013.

- ^ Variety staff (1965-01-01). "Review". Variety. Archived from the original on 2007-10-24. Retrieved 2007-07-30.

- ^ Thompson, Howard (October 28, 1965). "Movie Review: The Cincinnati Kid". The New York Times. Retrieved 2009-01-18.

- ^ "Mixed Deal". Time. November 5, 1965. Archived from the original on 2012-01-05. Retrieved 2009-01-18.

- ^ "The Cincinnati Kid". Rotten Tomatoes. Retrieved 13 August 2023.

External links

[edit]- 1965 films

- 1965 drama films

- American drama films

- Films based on American novels

- Films directed by Norman Jewison

- Films set in New Orleans

- Films set in the 1930s

- Films shot in New Orleans

- Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer films

- Films about poker

- Films with screenplays by Terry Southern

- Films with screenplays by Ring Lardner Jr.

- Films scored by Lalo Schifrin

- Filmways films

- Cockfighting in film

- 1960s English-language films

- 1960s American films

- English-language drama films